This is the eighth installment in our interview series with artists participating in the Look Here! Project. Rebecca Holderness is a director, choreographer, teacher and artistic director who has numerous productions to her credit, and an Associate Professor of Acting and Directing at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee's Peck School of the Arts. In this audio interview, she discusses a new work she created for the Look Here! Project, along with Andy Miller. Rebecca and Andy's installation will be part of the Look Here! exhibit at Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum, opening June 28th. There will be a public performance of their work at Villa Terrace on September 9, 2018.

The interview was conducted by Ann Hanlon, Head of UWM Libraries Digital Collections and Initiatives, on May 2, 2018 at the UWM Libraries Digital Humanities Lab Audio Studio.

A blog dedicated to highlighting the digital holdings of the UW-Milwaukee Libraries

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

Monday, May 21, 2018

The Look Here! Project: An Interview with Laj Waghray

This is the seventh installment in our interview series with artists participating in the Look Here! Project. Laj Waghray is a filmmaker; she is the Director of Red Crane Films, and has numerous documentaries to her credit, including "Sleepovers," a 2012 documentary about four girls growing into young adults; she co-directed the third film in Janet Fitch’s series, "Guns, Grief and Grace in America" (2009); co-produced Ramon Rivera-Moret’s documentary, "On Calloway Street" (2008); and worked as an associate producer for Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini’s "Well-Founded Fear" (2000). Waghray was the 2014 recipient of Kartemquin Films Diverse Voices in Docs fellowship.

Why were you interested in participating in the Look Here! Project?

I am a filmmaker and we often work in isolation. So when the Look Here! Project came up it was exciting as it presented me with an opportunity to be a part of a University Library and to work with people! This is a very good match for my personality.

AH: So when you’re talking about the research aspect of things – did you find in working on the Look Here! Project that working with the collections and materials helped to extend a current research project, or did it take you into something entirely new?

LW: I submitted two ideas when I first started the Look Here! Project. Both were something I had been exploring already. One idea was about the consequences of urbanization on bird habitats. I have been obsessed with that topic for a long time. And I’ve also been working on a short film which is more poetic, about ‘what hands do’. What do makers, or artists or whoever makes something with their hands - what draws them to their work, and why? So I submitted both ideas, thinking that my project with urbanization and birds will be the one that I would find the most material on and really, who was even thinking about hands? Then I come to the library and Max (Yela) is showing me these amazing artist books on similar issues and I realized there was much more material for the hands project. I was just blown away. Each book was part of this broad concept that I was exploring.

So that was an exciting discovery.

Then we talked about the Wisconsin Arts Project and the Milwaukee Handicrafts Project. What’s exciting is that someone, during the time of the Depression thought that jobs should come back and what did we go back to? Not technology but hands and handicrafts.

Yes, It was a federally funded program, I am researching the libraries collection of the work of Elsa Ulbricht, who devised and oversaw the nationally recognized Milwaukee Handicraft Project, an initiative created after the stock market crash that provided jobs for approximately 5,000 people (mostly poor, unskilled women), to manufacture toys, rugs, and printed fabrics.

The Idea was to provide employment for Americans affected by the economic crash through projects to improve the country’s infrastructure. Interestingly, it included a smaller project that focused on supporting the arts and involved people that were trained in working with their hands, which dovetailed nicely with my explorations.

AH: I actually always think of the word "work" with your project, but I don’t think that you are necessarily looking at it as just an issue of "work," in terms of what people are doing with their hands.

LW: It’s not just work. For some people it is just work -It’s not a choice. For many others though, It’s the making, it’s the process, and it’s the touch that is very satisfying.

A lot of these discoveries have been pretty exciting. I didn’t ever think manual work and handicrafts was something that a federal government would get involved in. The process is beautiful. It breaks your thinking pattern, it breaks your assumptions and you end up going a whole new direction from what you wanted to prove.

AH: So the challenges for you come from both the collections in the Library and from live people.

LW: Yes, It happened in most unexpected ways. There were some good challenges too, It was hard to concentrate at the Special collection library, it was somewhat akin to the being a kid in a candy store --- Everywhere you look there were stories coming at you. I had a hard time focusing but all my distractions and procrastination were tied to the fact that I might have succumbed to the temptation of turning pages of a book which is not related directly to my topic.

AH: In your previous work had you worked with historical materials very often?

LW: No, I’ve worked primarily with people. Sleepovers (2012) was about four girls and their journey. I followed them over the period of ten years. Then I worked on a film called On Calloway Street (2004), in New York, where I documented the lives of many immigrants over a period of two years. Later, I worked on a film on gun violence (Changing the Conversation: America’s Gun Violence Epidemic, 2009) and discovered that it’s not just homicide in urban populations which is the problem, but also suicides among white, suburban populations which goes under-reported. This is probably my first experience sitting in a library and digging, and I think I am hooked.

AH: You’ve talked about using the artist books that Max Yela has up in Special Collections, as well as the Milwaukee Arts Project collections, some of which we’ve digitized and put online. Are there any other collections that you’ve used that we haven’t talked about?

LW: Initially, for my urbanization and bird habitat project I found very interesting material like the Nehrling books, the Brehms Tierleben collection, and Eddee Daniel's artist books, which I hope to revisit later. Staying focused is a challenge when researching in a library like Special Collections.

AH: Do you save those up somehow for future reference?

LW: Yes, I do have this ‘idea book’ that I write things in. My challenge is that my work requires a team which requires funding. So if that comes along, I have lots of ideas in that book!

But going back to the challenge of focus, It’s very helpful that the librarians are interested in helping you, because sometimes research can be very overwhelming. I think the collaboration and getting to know the librarians; being able to go behind the scenes in the collections has been tremendous. The discussions with librarians lead you on the right path and they expand your ideas. They would have helped even if I was not part of a project, but this experience has been very rewarding.

AH: I think framing this as a project changes the relationship and makes it more of a partnership between the artists and the librarians than it might have been before. Which, like you said, the librarians would have always helped you. The Look Here! Project just makes it a more collaborative relationship.

LW: This time it seems like there’s this collaboration where the excitement is shared. It’s good. And the library has a stake in the work we’re creating.

AH: I think that’s exactly right. It’s not like you just walk away and show your work and we’re like "Oh that’s interesting. She used our stuff." We’re interested in what you’re doing with our stuff too. Because the other side of it for us is, how is that informing what we collect and what we digitize and how we make this material available so that it’s most useful for artists and others. Having you and other artists who work in a variety of media is contributing to our thinking on these things.

LW: It has made the experience quite rich, because I would have never thought of how Jill (Sebastian) is using the collections in her work, or Nirmal’s (Raja) use of the collections, or how Marc Tasman is repurposing things. When I’m listening to other artists it’s absolutely exciting.

AH: It’s been a really rich conversation. How did what you found in the collections influence your work?

LW: I had already decided when I applied how I was going to incorporate the materials. I did not expect that the collections would find me and change my work. I already knew what I was doing and thought I just needed X, Y, and Z to fulfill this task. Then I found all these artist books and the WPA projects - now I feel as if my project is advocating in some way for bringing the tactile sense back. I don’t know what will change in my journey. I’m on the journey where the work is talking to me. It is saying “Wait, you’re not done yet. You need to add me to your journey and you need to talk about what’s being done historically, too, and how are you going to do that?” That’s the challenge and that’s where I’m at right now, trying to figure that out.

How has having so much content available digitally affected the work you are creating or has it had any impact?

LW: One of the online collections I used was the Wisconsin Arts Project. While there is a lot of material it’s very nicely organized so it’s a little less overwhelming. Still, because I’m going directly to where I want, there is a fear that I might be missing something else. In the Special Collections library what I wanted was put out on the table for me. I called Max and when I’d arrive it was already set out, so when you go to the library you are looking at your resources and your work – but there is also all the other work that other people are working on around you. Whether they’re there or not, the traces of their work are there. An unopened book there, a closed box with an interesting title. I found a film index from a few years back. There was some collection of encyclopedias from India that were old. I really had to pull myself back and say, “Max put this out for you on the table – there are 15 books out on the table; sit there and look at them.”

AH: But was it exciting to have that other work sort of radiating around you?

LW: Yes, it’s like you’re surrounded by the evidence of other people’s ideas. If we are open to be influenced by other people's ideas we can arrive at a balance where their ideas can infiltrate into your curiosity and can unexpectedly elevate your project, making the process dynamic, ever-changing and exciting.

Why were you interested in participating in the Look Here! Project?

I am a filmmaker and we often work in isolation. So when the Look Here! Project came up it was exciting as it presented me with an opportunity to be a part of a University Library and to work with people! This is a very good match for my personality.

AH: So when you’re talking about the research aspect of things – did you find in working on the Look Here! Project that working with the collections and materials helped to extend a current research project, or did it take you into something entirely new?

LW: I submitted two ideas when I first started the Look Here! Project. Both were something I had been exploring already. One idea was about the consequences of urbanization on bird habitats. I have been obsessed with that topic for a long time. And I’ve also been working on a short film which is more poetic, about ‘what hands do’. What do makers, or artists or whoever makes something with their hands - what draws them to their work, and why? So I submitted both ideas, thinking that my project with urbanization and birds will be the one that I would find the most material on and really, who was even thinking about hands? Then I come to the library and Max (Yela) is showing me these amazing artist books on similar issues and I realized there was much more material for the hands project. I was just blown away. Each book was part of this broad concept that I was exploring.

So that was an exciting discovery.

Then we talked about the Wisconsin Arts Project and the Milwaukee Handicrafts Project. What’s exciting is that someone, during the time of the Depression thought that jobs should come back and what did we go back to? Not technology but hands and handicrafts.

AH: That’s interesting, and that’s the Milwaukee Arts Project?

Yes, It was a federally funded program, I am researching the libraries collection of the work of Elsa Ulbricht, who devised and oversaw the nationally recognized Milwaukee Handicraft Project, an initiative created after the stock market crash that provided jobs for approximately 5,000 people (mostly poor, unskilled women), to manufacture toys, rugs, and printed fabrics.

The Idea was to provide employment for Americans affected by the economic crash through projects to improve the country’s infrastructure. Interestingly, it included a smaller project that focused on supporting the arts and involved people that were trained in working with their hands, which dovetailed nicely with my explorations.

AH: I actually always think of the word "work" with your project, but I don’t think that you are necessarily looking at it as just an issue of "work," in terms of what people are doing with their hands.

LW: It’s not just work. For some people it is just work -It’s not a choice. For many others though, It’s the making, it’s the process, and it’s the touch that is very satisfying.

A lot of these discoveries have been pretty exciting. I didn’t ever think manual work and handicrafts was something that a federal government would get involved in. The process is beautiful. It breaks your thinking pattern, it breaks your assumptions and you end up going a whole new direction from what you wanted to prove.

AH: So the challenges for you come from both the collections in the Library and from live people.

LW: Yes, It happened in most unexpected ways. There were some good challenges too, It was hard to concentrate at the Special collection library, it was somewhat akin to the being a kid in a candy store --- Everywhere you look there were stories coming at you. I had a hard time focusing but all my distractions and procrastination were tied to the fact that I might have succumbed to the temptation of turning pages of a book which is not related directly to my topic.

LW: No, I’ve worked primarily with people. Sleepovers (2012) was about four girls and their journey. I followed them over the period of ten years. Then I worked on a film called On Calloway Street (2004), in New York, where I documented the lives of many immigrants over a period of two years. Later, I worked on a film on gun violence (Changing the Conversation: America’s Gun Violence Epidemic, 2009) and discovered that it’s not just homicide in urban populations which is the problem, but also suicides among white, suburban populations which goes under-reported. This is probably my first experience sitting in a library and digging, and I think I am hooked.

AH: You’ve talked about using the artist books that Max Yela has up in Special Collections, as well as the Milwaukee Arts Project collections, some of which we’ve digitized and put online. Are there any other collections that you’ve used that we haven’t talked about?

LW: Initially, for my urbanization and bird habitat project I found very interesting material like the Nehrling books, the Brehms Tierleben collection, and Eddee Daniel's artist books, which I hope to revisit later. Staying focused is a challenge when researching in a library like Special Collections.

AH: Do you save those up somehow for future reference?

LW: Yes, I do have this ‘idea book’ that I write things in. My challenge is that my work requires a team which requires funding. So if that comes along, I have lots of ideas in that book!

But going back to the challenge of focus, It’s very helpful that the librarians are interested in helping you, because sometimes research can be very overwhelming. I think the collaboration and getting to know the librarians; being able to go behind the scenes in the collections has been tremendous. The discussions with librarians lead you on the right path and they expand your ideas. They would have helped even if I was not part of a project, but this experience has been very rewarding.

AH: I think framing this as a project changes the relationship and makes it more of a partnership between the artists and the librarians than it might have been before. Which, like you said, the librarians would have always helped you. The Look Here! Project just makes it a more collaborative relationship.

LW: This time it seems like there’s this collaboration where the excitement is shared. It’s good. And the library has a stake in the work we’re creating.

AH: I think that’s exactly right. It’s not like you just walk away and show your work and we’re like "Oh that’s interesting. She used our stuff." We’re interested in what you’re doing with our stuff too. Because the other side of it for us is, how is that informing what we collect and what we digitize and how we make this material available so that it’s most useful for artists and others. Having you and other artists who work in a variety of media is contributing to our thinking on these things.

LW: It has made the experience quite rich, because I would have never thought of how Jill (Sebastian) is using the collections in her work, or Nirmal’s (Raja) use of the collections, or how Marc Tasman is repurposing things. When I’m listening to other artists it’s absolutely exciting.

AH: It’s been a really rich conversation. How did what you found in the collections influence your work?

LW: I had already decided when I applied how I was going to incorporate the materials. I did not expect that the collections would find me and change my work. I already knew what I was doing and thought I just needed X, Y, and Z to fulfill this task. Then I found all these artist books and the WPA projects - now I feel as if my project is advocating in some way for bringing the tactile sense back. I don’t know what will change in my journey. I’m on the journey where the work is talking to me. It is saying “Wait, you’re not done yet. You need to add me to your journey and you need to talk about what’s being done historically, too, and how are you going to do that?” That’s the challenge and that’s where I’m at right now, trying to figure that out.

How has having so much content available digitally affected the work you are creating or has it had any impact?

LW: One of the online collections I used was the Wisconsin Arts Project. While there is a lot of material it’s very nicely organized so it’s a little less overwhelming. Still, because I’m going directly to where I want, there is a fear that I might be missing something else. In the Special Collections library what I wanted was put out on the table for me. I called Max and when I’d arrive it was already set out, so when you go to the library you are looking at your resources and your work – but there is also all the other work that other people are working on around you. Whether they’re there or not, the traces of their work are there. An unopened book there, a closed box with an interesting title. I found a film index from a few years back. There was some collection of encyclopedias from India that were old. I really had to pull myself back and say, “Max put this out for you on the table – there are 15 books out on the table; sit there and look at them.”

AH: But was it exciting to have that other work sort of radiating around you?

LW: Yes, it’s like you’re surrounded by the evidence of other people’s ideas. If we are open to be influenced by other people's ideas we can arrive at a balance where their ideas can infiltrate into your curiosity and can unexpectedly elevate your project, making the process dynamic, ever-changing and exciting.

Monday, April 23, 2018

The Look Here! Project: An Interview with Jill Sebastian

This is the fifth installment in our interview series with artists participating in the Look Here! project. Jill Sebastian is Professor Emerita at the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. She has received numerous awards, including an NEA Fellowship, and the City of Milwaukee's Artist of the Year Award (1997). She has completed public art installations in Milwaukee, Madison, and New Orleans, and her work has been exhibited nationally.

Why were you interested in participating in the Look Here! pilot project?

Much of my work involves a dialectical overlay between physical experience and conceptual subtext. Whereas I may do extensive "needle-in-the-haystack" trolling of cultural context, history, politics to map my ideas, as an object maker I am still riveted by the rare, the firsthand experiencing of things. AGSL (The American Geographical Society Library) and the UWM Special Collections' rich, unique artifacts presented the possibility of adventure, exploring territories rarely visited and holding them to the light of now.

What collections are using or did you begin to use for your project?

Where I began as an explorer is not where we will arrive in the final work.

My initial proposal was to use the Brumder and the Civil Rights collections to flesh out a children's book in progress - a primer on voting rights. Raking through the archives added a few important details to the project, which I will use, but my overall continuing research would lead me quite afield from the collections. Once Look Here! introduced us to the prospect of exhibiting at Villa Terrace, I felt the opportunity would better be used to connect to major ongoing threads within my studio work - the distribution of protectionist propaganda with migration/invasion of plant and wildlife - to the research opportunity.

My initial proposal was to use the Brumder and the Civil Rights collections to flesh out a children's book in progress - a primer on voting rights. Raking through the archives added a few important details to the project, which I will use, but my overall continuing research would lead me quite afield from the collections. Once Look Here! introduced us to the prospect of exhibiting at Villa Terrace, I felt the opportunity would better be used to connect to major ongoing threads within my studio work - the distribution of protectionist propaganda with migration/invasion of plant and wildlife - to the research opportunity.

The Brumder publishing collection with its emphasis on familiarizing and situating the 19th century, immigrant German population in their new locale, Milwaukee, once gave a widely needed framework of belonging, influence and assumed regional values. I looked at far more than I could ever use but settled on Our native birds of song and beauty by H. Nehring.

Casting a wide net helped me gather a bounty which I can winnow - eliminating this option or that, focusing to a multi-layered simplicity; considering whether what I envision has been done or not, giving authentic context for my effort and finally being reassured that I am pursuing a new path.

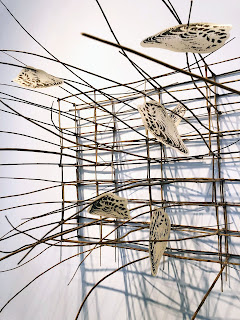

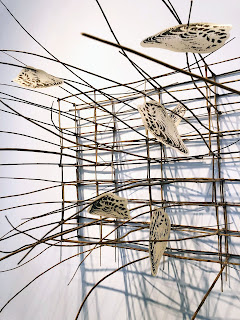

I will be doing an installation in Villa Terrace's Zuber room with its Chinoise wallpaper printed by hand from 500 wood blocks dating back to 1795. I have looked carefully at holdings in original artists' woodcuts. I think Max Yela (Curator, UWM Special Collections) saw the relevance of my papermaking in the larger context of artists books and works on or about paper before I did.

Since the Zuber room is centered to overlook an Italian inspired garden, I expanded into meanings of garden design - The Art of Garden Design in Italy by H. Inigo Triggs and ASGL photographs of the Gardens of Babur in Kabul (Bagh-e Babur). Destroyed in war this Islamic garden was built along a center stepped spine of water in the 1500s as a reminder of paradise and became an influence on Renaissance thought.

How did what you found in the collections influence your work?

Because I have strong trajectories in my practice, I worked to connect the collection to what I am doing, rather than approaching without a concept looking for inspiration. This means a much longer process of research to find what resonates, what deepens through threads of connections over time. I admit this has been sometimes a struggle with optimistic starts that did not pan out, but the librarians were always excited to suggest, "Have you seen this?" or "Maybe you would find this valuable." Their guidance has been the most valuable asset.

How does having so much content available digitally affect the work you're creating? Or does it?

I began my research with an exhibition on Brumder Publishing and the actual artifacts. Special Collections offered to digitize any holdings, and scanning Nehring's Birds became a foundation for my project. Perhaps the biggest advantage was in culling through the online catalogue of holdings and seeing images there that opened up new avenues of research.

I began my research with an exhibition on Brumder Publishing and the actual artifacts. Special Collections offered to digitize any holdings, and scanning Nehring's Birds became a foundation for my project. Perhaps the biggest advantage was in culling through the online catalogue of holdings and seeing images there that opened up new avenues of research.

The high quality of the images meant that I could work directly with information rich files. To pry open the singularity of one-of-a-kind artifacts, books, engravings, to share them broadly. And yet, my work - despite digitally laser cutting woodblocks and several hundred prints - will be synthesized into a fragile, temporary, first-hand physical nature of a site-specific installation. The expansion and contraction of experience is the irony of our digital age.

What more can you tell us about your experience in this project?

Knowing that the work from Look Here! would be shared in an exhibition in a venue, Villa Terrace, laden with rich history impacted the direction of my project.

We romanticize nature, and we idealize it in gardens. Right in front of us on a micro level are ongoing lessons of life and death, war and peace, heaven and hell found by closely considering a small plot of earth.

The Zuber Room at the Villa Terrace is papered with handprinted scenes of an exotic Chinoise paradise. My site-specific installation will inject realities of the garden world outside where drab Wisconsin Sparrows have been harvested for culinary pleasure; Red Wing Blackbirds fiercely defend their territory; Tree of Heaven Sumac, Wild Mustard, Burdock and Thistle invade, threatening the order of a perfect world; and where the continuing war in Afganistan seems remote, unreal.

======

More about Jill Sebastian's work is here: http://jillsebastian.com/

Why were you interested in participating in the Look Here! pilot project?

Much of my work involves a dialectical overlay between physical experience and conceptual subtext. Whereas I may do extensive "needle-in-the-haystack" trolling of cultural context, history, politics to map my ideas, as an object maker I am still riveted by the rare, the firsthand experiencing of things. AGSL (The American Geographical Society Library) and the UWM Special Collections' rich, unique artifacts presented the possibility of adventure, exploring territories rarely visited and holding them to the light of now.

What collections are using or did you begin to use for your project?

Where I began as an explorer is not where we will arrive in the final work.

My initial proposal was to use the Brumder and the Civil Rights collections to flesh out a children's book in progress - a primer on voting rights. Raking through the archives added a few important details to the project, which I will use, but my overall continuing research would lead me quite afield from the collections. Once Look Here! introduced us to the prospect of exhibiting at Villa Terrace, I felt the opportunity would better be used to connect to major ongoing threads within my studio work - the distribution of protectionist propaganda with migration/invasion of plant and wildlife - to the research opportunity.

My initial proposal was to use the Brumder and the Civil Rights collections to flesh out a children's book in progress - a primer on voting rights. Raking through the archives added a few important details to the project, which I will use, but my overall continuing research would lead me quite afield from the collections. Once Look Here! introduced us to the prospect of exhibiting at Villa Terrace, I felt the opportunity would better be used to connect to major ongoing threads within my studio work - the distribution of protectionist propaganda with migration/invasion of plant and wildlife - to the research opportunity.The Brumder publishing collection with its emphasis on familiarizing and situating the 19th century, immigrant German population in their new locale, Milwaukee, once gave a widely needed framework of belonging, influence and assumed regional values. I looked at far more than I could ever use but settled on Our native birds of song and beauty by H. Nehring.

Casting a wide net helped me gather a bounty which I can winnow - eliminating this option or that, focusing to a multi-layered simplicity; considering whether what I envision has been done or not, giving authentic context for my effort and finally being reassured that I am pursuing a new path.

|

| Zuber Gallery at Villa Terrace |

Since the Zuber room is centered to overlook an Italian inspired garden, I expanded into meanings of garden design - The Art of Garden Design in Italy by H. Inigo Triggs and ASGL photographs of the Gardens of Babur in Kabul (Bagh-e Babur). Destroyed in war this Islamic garden was built along a center stepped spine of water in the 1500s as a reminder of paradise and became an influence on Renaissance thought.

How did what you found in the collections influence your work?

Because I have strong trajectories in my practice, I worked to connect the collection to what I am doing, rather than approaching without a concept looking for inspiration. This means a much longer process of research to find what resonates, what deepens through threads of connections over time. I admit this has been sometimes a struggle with optimistic starts that did not pan out, but the librarians were always excited to suggest, "Have you seen this?" or "Maybe you would find this valuable." Their guidance has been the most valuable asset.

How does having so much content available digitally affect the work you're creating? Or does it?

I began my research with an exhibition on Brumder Publishing and the actual artifacts. Special Collections offered to digitize any holdings, and scanning Nehring's Birds became a foundation for my project. Perhaps the biggest advantage was in culling through the online catalogue of holdings and seeing images there that opened up new avenues of research.

I began my research with an exhibition on Brumder Publishing and the actual artifacts. Special Collections offered to digitize any holdings, and scanning Nehring's Birds became a foundation for my project. Perhaps the biggest advantage was in culling through the online catalogue of holdings and seeing images there that opened up new avenues of research.The high quality of the images meant that I could work directly with information rich files. To pry open the singularity of one-of-a-kind artifacts, books, engravings, to share them broadly. And yet, my work - despite digitally laser cutting woodblocks and several hundred prints - will be synthesized into a fragile, temporary, first-hand physical nature of a site-specific installation. The expansion and contraction of experience is the irony of our digital age.

What more can you tell us about your experience in this project?

Knowing that the work from Look Here! would be shared in an exhibition in a venue, Villa Terrace, laden with rich history impacted the direction of my project.

We romanticize nature, and we idealize it in gardens. Right in front of us on a micro level are ongoing lessons of life and death, war and peace, heaven and hell found by closely considering a small plot of earth.

The Zuber Room at the Villa Terrace is papered with handprinted scenes of an exotic Chinoise paradise. My site-specific installation will inject realities of the garden world outside where drab Wisconsin Sparrows have been harvested for culinary pleasure; Red Wing Blackbirds fiercely defend their territory; Tree of Heaven Sumac, Wild Mustard, Burdock and Thistle invade, threatening the order of a perfect world; and where the continuing war in Afganistan seems remote, unreal.

======

More about Jill Sebastian's work is here: http://jillsebastian.com/

Monday, April 2, 2018

The Look Here! Project: An interview with Anja Sieger

This is the fifth installment in our interview series with artists participating in the Look Here! project. Anja Notanja Sieger is an improv artist and writer who uses multiple media and performance. She is an Artist in Residence at RedLine Milwaukee, and was Resident Narrator at the Pfister Hotel in 2014-2015.

Why were you interested in participating in this Look Here! pilot project?

I really like libraries, research, images, learning, and then with this project, having parameters within which to make artwork so I’m not just inventing everything. I like rules. The Look Here! project has a broad charge but the main restriction is that the inspiration needs to come from the digital collections. And I like that because I feel that I'm magnetically pulled to books – and even though the digital library isn’t per se a book, it has that attraction for me in that it’s access to a bunch of things that you have to wade through to understand; texts, images, documents.

What collections are using or did you begin to use for your project?

Originally I was very drawn to the American Geographical Society Library (AGSL) collections specifically because they could take you anywhere in the world that you wanted to go and you’d never have the same thing going on. But since then I’ve based my work around the tarot deck, and I have new parameters of trying to find anything related to the current tarot card that I’m working on. Tarot cards are an ancient picture system that tell a story of someone going on a journey and having basically a whole life cycle of experiences. Each of the cards has traditionally associated with different meanings. So I try to look into the traditional meaning of that card, and then I try to see if I can find a picture anywhere in the digital archive that meets that parameter. If I can, I want them to be wearing a hat because my whole theme within the tarot deck is hats - so I have to have a hat, I have to have a digital picture, I have to have the theme of the tarot card, and then I have to interpret it in a way where I like the meaning and the way it looks and the composition. So there are about four factors that constrict me and I really like that because before I didn’t have any rules as to what I was finding, and that fizzled out because I didn’t have the rigor with that, that having these four rules provide.

Is rule-making always part of your project/process?

It kind of is my process – what I’ve done is always improvisational. So I don’t usually plan things out a lot; so when I am cutting paper I just have a scissors and a piece of paper and that is my rule – I can only do something with scissors and a piece of paper. Or when I’m out typing – which is what most people locally might know me for – I have the person, I have what they want, I have a typewriter, and I have 10 minutes. So I kind of like higher-stakes projects.

Since you’re more well-known for the typing project and that’s machine-oriented, have you thought of that with regard to the digital aspect of this project?

No real connection except that there isn’t one. I’ve taken three months off from commissions and working for other people, and checking Facebook a lot, and seeing what happens when I’m not online and if I don’t have previous engagements. And, apparently, using pen and ink, drawing tarot, doing collage, and using Cray-pas thus far is the answer to what happens!

How did what you found in the collections influence your work?

One of my cards is the wheel of fortune, so I would just type the word "wheel" into the digital collections search engine and find something. Since then I’ve worked with the (Milwaukee) Polonia collections, the ARCW (AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin) collection, the (James Blair) Murdoch photographs, the Golda Meir collection, and the AGSL photo collections.

You were able to take not just the images in the collection but the construct of the collection – the fact that it’s vast, and just approach it randomly with a keyword search.

It’s kind of natural to me because I am of the generation that probably started Googling things when I was in 7th grade, so I’m a Googler – that’s my main way of doing research. Of course I used card catalogs growing up, but Google is the technique I’m most familiar with. It’s efficient. It’s the same process I would use normally if I wanted to find out anything – even though I’m on a social media break, I still retain the knowledge I gained using social media. So searching through the collections, I know these librarians probably used a particular tag to describe an image, for example, and I can use that to find other images.

When I was interpreting the hanged man card – that subject or image could be very delicate. Do I want to take a picture of lynching and interpret it? Probably not for this project. I had to think about, "what is another way people hang upside down?" I thought of gymnasts – and there are some gymnast photos in the Polonia collection. And then I just needed an interpretation of the act of hanging from something, with a tree as part of the image. It’s actually very creepy looking but at the same time I’m not appropriating anything horrible that happened to someone. It makes it a different piece at that point and I don’t think I have the authority to make such a piece. [note: The source image for this card ultimately came from the James Blair Murdoch collection]

In this example, when you thought about gymnasts as an alternative, did you think – oh I’ve seen this in Polonia?

No, I just typed in "gymnast" and then I limited to just images and the Polonia collection came up. And he wasn’t wearing a hat so I decided to make it a hat that he was actually hanging from. It’s interesting because I feel a certain connection to the Polonia collection because I went to school at 5th and Mitchell from K-8 and I would walk up and down Mitchell Street and I feel like I know that neighborhood pretty well, and I’m Polish so some of these people could be my ancestors. It’s also a vast collection – your chances of finding things that can be used are pretty good. And interesting to see what’s still around in Milwaukee, and what's disappeared.

How does having so much content available digitally affect the work you're creating?

I’m really having to let go of trying to control the image. I would say the digital collection has the

biggest impact on what the image is going to look like. I don’t do any predesigning of the card. I do some research on the tradition of the card, and then I try and sum up the meaning in images. For example, in the traditional judgment card, it's a picture of a bunch of people rising out of coffins, skies opening up, there’s a big horn – traditionally the interpretation of the card is something like your "true calling," rising up out of your deadened state to become who you're meant to be. So then I thought of what the idea of true calling is, and what does that look like as an image? And then I thought of a phone call. So I started looking for pictures of people on the telephone, and then I found this woman who is on the phone with a calendar behind her, but I still needed to find other images that relate to the original judgement card, so I added gnomes around her and other images of getting ready to go to work, gnomes who can help you get something done.

I like looking at the cards as archetypes and then I try to replicate that archetype in any way using the digital collections – so I’m really finding archetypes in the digital collections. It’s a new way to use the digital collections – for archetype-finding.

Even though the digital collections are vast, I’ll do a search and then sometimes nothing pops up that’s related, but it’s still productive. For example, I tried to do a search for "gambling" when I was interpreting the four of pentacles card. All of the pentacle cards are a suit that in your normal playing card deck – which are the same thing but at one point they split off in their history. So four of pentacles are the same as four of diamonds, and this is about money and worldly goods. The four of pentacles is traditionally about being stable with your money but also having enough to be able to do something with it and not hoard it. So who is someone who might hoard money, and I thought of gamblers. When I searched the collection I was hoping for some Las Vegas gambler but what I got were some really interesting images of people in Asia with a wheel of fortune device or elsewhere with wheels, but I was looking for were more like images of money exchange, or those chips. I did find people going to banks, making transactions. So it's a vast collection but not infinite. It means I need to redefine my search or my card and so the digital collection ends up completely defining what my archetype is going to be for the card.

And so you really confined yourself to the digital collection in a way others haven’t necessarily done; you’re doing a project that really is only mediated by the digital collection. You aren’t going in and asking reference questions – you’re working from this as a database and the source for your work.

Sometimes I think I’ll want to do another tarot deck where I choose the imagery more, but in doing it this way I really have to think about what is the essence of something, and I’ll have to completely change it because it was getting too complicated. Because tarot cards are from pre-literate society you have to get the whole meaning from looking at it, so you have to keep things simple. I recently drew an entire card and it was beautiful but when I looked at it I didn’t think anyone could tell what it was about so I had to scrap it.

When you’re searching in the digital collection for something, is that similar for you to pulling a card from the deck – where you don’t know what you’re going to get but you’re going to work with it? Is that part of your approach?

Yes, it’s almost like divining – an image comes to you from the archive. You do the search, and it sometimes is a random process. A lot of people think of the tarot deck as a conduit of the spirit giving you a message from your unconscious. So I think of the digital archive as a conduit of the spirit or the unconscious.

It’s a mystification of the digital collection that isn’t usually how we think of the deliberate work of creating these digital collections, but that seems entirely appropriate in the context of the project.

Any project I work on has to do with divining and letting the unconscious bleed and then seeing what happens when you clean up that mess. It’s interesting to do this with library collections – where the library is all about organizing and cleaning up what might have been a mess, and so this is an interesting process to lay on top of library collections that really resist disorganization; but going ahead and letting it be random. There is an expectation that we respond to a specific collection in the library, but I’m much more interested in what falls out as I shuffle the cards.

What more can you tell us about your experience in this project?

I think that a lot of people are really freaked out by the tarot, but I’m not. And as I do this work, I think the whole process is really interesting because how often do we get to interact with archetypes in our lives, in a deliberate way? It’s interesting because I’m almost exclusively using photographs as my source materials, so the images I’m drawing are based on real life. It’s like discovering how in any given moment you can be living in an archetype and it calls attention to the archetype of the moment as something you are experiencing and learning from. If anything, this process has more to do with the past and bringing it into the present. This has nothing to do with the future.

======

More about Anja Notanja Sieger's work is here: http://www.laprosette.com/

Why were you interested in participating in this Look Here! pilot project?

I really like libraries, research, images, learning, and then with this project, having parameters within which to make artwork so I’m not just inventing everything. I like rules. The Look Here! project has a broad charge but the main restriction is that the inspiration needs to come from the digital collections. And I like that because I feel that I'm magnetically pulled to books – and even though the digital library isn’t per se a book, it has that attraction for me in that it’s access to a bunch of things that you have to wade through to understand; texts, images, documents.

What collections are using or did you begin to use for your project?

Originally I was very drawn to the American Geographical Society Library (AGSL) collections specifically because they could take you anywhere in the world that you wanted to go and you’d never have the same thing going on. But since then I’ve based my work around the tarot deck, and I have new parameters of trying to find anything related to the current tarot card that I’m working on. Tarot cards are an ancient picture system that tell a story of someone going on a journey and having basically a whole life cycle of experiences. Each of the cards has traditionally associated with different meanings. So I try to look into the traditional meaning of that card, and then I try to see if I can find a picture anywhere in the digital archive that meets that parameter. If I can, I want them to be wearing a hat because my whole theme within the tarot deck is hats - so I have to have a hat, I have to have a digital picture, I have to have the theme of the tarot card, and then I have to interpret it in a way where I like the meaning and the way it looks and the composition. So there are about four factors that constrict me and I really like that because before I didn’t have any rules as to what I was finding, and that fizzled out because I didn’t have the rigor with that, that having these four rules provide.

Is rule-making always part of your project/process?

It kind of is my process – what I’ve done is always improvisational. So I don’t usually plan things out a lot; so when I am cutting paper I just have a scissors and a piece of paper and that is my rule – I can only do something with scissors and a piece of paper. Or when I’m out typing – which is what most people locally might know me for – I have the person, I have what they want, I have a typewriter, and I have 10 minutes. So I kind of like higher-stakes projects.

Since you’re more well-known for the typing project and that’s machine-oriented, have you thought of that with regard to the digital aspect of this project?

No real connection except that there isn’t one. I’ve taken three months off from commissions and working for other people, and checking Facebook a lot, and seeing what happens when I’m not online and if I don’t have previous engagements. And, apparently, using pen and ink, drawing tarot, doing collage, and using Cray-pas thus far is the answer to what happens!

How did what you found in the collections influence your work?

One of my cards is the wheel of fortune, so I would just type the word "wheel" into the digital collections search engine and find something. Since then I’ve worked with the (Milwaukee) Polonia collections, the ARCW (AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin) collection, the (James Blair) Murdoch photographs, the Golda Meir collection, and the AGSL photo collections.

You were able to take not just the images in the collection but the construct of the collection – the fact that it’s vast, and just approach it randomly with a keyword search.

It’s kind of natural to me because I am of the generation that probably started Googling things when I was in 7th grade, so I’m a Googler – that’s my main way of doing research. Of course I used card catalogs growing up, but Google is the technique I’m most familiar with. It’s efficient. It’s the same process I would use normally if I wanted to find out anything – even though I’m on a social media break, I still retain the knowledge I gained using social media. So searching through the collections, I know these librarians probably used a particular tag to describe an image, for example, and I can use that to find other images.

When I was interpreting the hanged man card – that subject or image could be very delicate. Do I want to take a picture of lynching and interpret it? Probably not for this project. I had to think about, "what is another way people hang upside down?" I thought of gymnasts – and there are some gymnast photos in the Polonia collection. And then I just needed an interpretation of the act of hanging from something, with a tree as part of the image. It’s actually very creepy looking but at the same time I’m not appropriating anything horrible that happened to someone. It makes it a different piece at that point and I don’t think I have the authority to make such a piece. [note: The source image for this card ultimately came from the James Blair Murdoch collection]

In this example, when you thought about gymnasts as an alternative, did you think – oh I’ve seen this in Polonia?

No, I just typed in "gymnast" and then I limited to just images and the Polonia collection came up. And he wasn’t wearing a hat so I decided to make it a hat that he was actually hanging from. It’s interesting because I feel a certain connection to the Polonia collection because I went to school at 5th and Mitchell from K-8 and I would walk up and down Mitchell Street and I feel like I know that neighborhood pretty well, and I’m Polish so some of these people could be my ancestors. It’s also a vast collection – your chances of finding things that can be used are pretty good. And interesting to see what’s still around in Milwaukee, and what's disappeared.

How does having so much content available digitally affect the work you're creating?

|

biggest impact on what the image is going to look like. I don’t do any predesigning of the card. I do some research on the tradition of the card, and then I try and sum up the meaning in images. For example, in the traditional judgment card, it's a picture of a bunch of people rising out of coffins, skies opening up, there’s a big horn – traditionally the interpretation of the card is something like your "true calling," rising up out of your deadened state to become who you're meant to be. So then I thought of what the idea of true calling is, and what does that look like as an image? And then I thought of a phone call. So I started looking for pictures of people on the telephone, and then I found this woman who is on the phone with a calendar behind her, but I still needed to find other images that relate to the original judgement card, so I added gnomes around her and other images of getting ready to go to work, gnomes who can help you get something done.

I like looking at the cards as archetypes and then I try to replicate that archetype in any way using the digital collections – so I’m really finding archetypes in the digital collections. It’s a new way to use the digital collections – for archetype-finding.

Even though the digital collections are vast, I’ll do a search and then sometimes nothing pops up that’s related, but it’s still productive. For example, I tried to do a search for "gambling" when I was interpreting the four of pentacles card. All of the pentacle cards are a suit that in your normal playing card deck – which are the same thing but at one point they split off in their history. So four of pentacles are the same as four of diamonds, and this is about money and worldly goods. The four of pentacles is traditionally about being stable with your money but also having enough to be able to do something with it and not hoard it. So who is someone who might hoard money, and I thought of gamblers. When I searched the collection I was hoping for some Las Vegas gambler but what I got were some really interesting images of people in Asia with a wheel of fortune device or elsewhere with wheels, but I was looking for were more like images of money exchange, or those chips. I did find people going to banks, making transactions. So it's a vast collection but not infinite. It means I need to redefine my search or my card and so the digital collection ends up completely defining what my archetype is going to be for the card.

And so you really confined yourself to the digital collection in a way others haven’t necessarily done; you’re doing a project that really is only mediated by the digital collection. You aren’t going in and asking reference questions – you’re working from this as a database and the source for your work.

Sometimes I think I’ll want to do another tarot deck where I choose the imagery more, but in doing it this way I really have to think about what is the essence of something, and I’ll have to completely change it because it was getting too complicated. Because tarot cards are from pre-literate society you have to get the whole meaning from looking at it, so you have to keep things simple. I recently drew an entire card and it was beautiful but when I looked at it I didn’t think anyone could tell what it was about so I had to scrap it.

When you’re searching in the digital collection for something, is that similar for you to pulling a card from the deck – where you don’t know what you’re going to get but you’re going to work with it? Is that part of your approach?

Yes, it’s almost like divining – an image comes to you from the archive. You do the search, and it sometimes is a random process. A lot of people think of the tarot deck as a conduit of the spirit giving you a message from your unconscious. So I think of the digital archive as a conduit of the spirit or the unconscious.

It’s a mystification of the digital collection that isn’t usually how we think of the deliberate work of creating these digital collections, but that seems entirely appropriate in the context of the project.

Any project I work on has to do with divining and letting the unconscious bleed and then seeing what happens when you clean up that mess. It’s interesting to do this with library collections – where the library is all about organizing and cleaning up what might have been a mess, and so this is an interesting process to lay on top of library collections that really resist disorganization; but going ahead and letting it be random. There is an expectation that we respond to a specific collection in the library, but I’m much more interested in what falls out as I shuffle the cards.

What more can you tell us about your experience in this project?

I think that a lot of people are really freaked out by the tarot, but I’m not. And as I do this work, I think the whole process is really interesting because how often do we get to interact with archetypes in our lives, in a deliberate way? It’s interesting because I’m almost exclusively using photographs as my source materials, so the images I’m drawing are based on real life. It’s like discovering how in any given moment you can be living in an archetype and it calls attention to the archetype of the moment as something you are experiencing and learning from. If anything, this process has more to do with the past and bringing it into the present. This has nothing to do with the future.

======

More about Anja Notanja Sieger's work is here: http://www.laprosette.com/

Thursday, February 1, 2018

The Look Here! project: An interview with Madeline Martin

This is the fourth installment in our interview series with artists participating in the Look Here! project. Madeline Martin, an MFA candidate at UW-Milwaukee, is a watercolor, paper, and embroidery artist. Her work honors everyday people by commemorating their intimate and familial moments through rich and layered details. Her work has been exhibited across the United States. In addition to raising her three young children, she was an art teacher at the Boys & Girls Club in Milwaukee’s Sherman Park for five years, an artist-in-residence at RedLine Milwaukee, and a teacher for disabled adults in the Twin Cities.

Why were you interested in participating in the Look Here!

project?

I was initially

interested in participating in the Look Here! Project because of the blend of

RedLine Milwaukee artists and UWM faculty. I was an artist-in-residence at RedLine from 2011-2013, and I am

currently an MFA candidate at UWM. The

union of both groups felt like a welcome congruence in the beginning of my grad

program. I also was confident that I

could make something based on the library’s cache of knowledge; an artist

could truly spend an entire career working with the UWM Library’s materials.

What collections are you using or did you begin to use for

your work?

I initially planned to make work related to the

library’s watercolor period paintings found in the Work Progress Administration Collection. Since a lot of my work has

focused on embroidered and watercolor portraits, I was intrigued by the

different names applied to pieces in the library’s collection, such as "EuropeanPeasant," or "Civil War Child." I thought I could apply those same titles to Milwaukee

community members in a contemporary context. As I delved deeper into this project, though,

I concluded that those titles were applicable to theater characters but

somewhat reductive for actual people. That collection was a fruitful origin

point, however, and it served as a stepping stone for later research.

How did what you found in the collections influence your

work?

In the American Geographical Society Library, I

was impressed/overwhelmed by the vast amount of information, but I was most

amazed by the fact that the AGSL staff will print images onto fabric and a

variety of paper for a reasonable price. The AGSL is a treasure for artists and

researchers, and I will be utilizing some of its topographical maps and aerial

imagery in this project as a way to connect the people whom I am featuring with

ancestral lands.

I also spent time with the UWM Archive's Vel Phillips collection, which features some of her personal family photo albums

alongside content related to her career and civil rights history. While I may not use any of the archived images

directly in my work, Vel Phillips’ professionalism and commitment to her family

and community inspired me during this project. The archives contain a photo of Judge Phillips

tying her son’s shoes, and a scanned image of that photo hangs above my desk. That image has kept me company while I work,

reminding me that mothering and parenting, although a common activity, is still

profoundly sacred. Despite its endless

minutiae, parenting has effects we can never fully understand. I am grateful

for the role model of Vel Phillips, a mother who still maintained her

commitment to justice and community. Her

work towards equality could arguably be considered an extension of her role as

a mother, ensuring a better life for her children and grandchildren,

simultaneously weaving together the past and the future.

How does having so much content

available digitally affect the work you're creating?

Digital

images have immense power and provide a way to continually revisit a piece, but

I still appreciate the physical nature of touching books, maps, and archives in

the library. For me, material interactions

usually inspire greater reflection than online viewing. In my research, I especially found the books

related to family in the Special Collections helpful as I navigate the creation

of work that is often very private but offered to the public sphere. Those

included Argentine artist Silvia Guigon's 2011

homage to her grandmother, Amanda (La mujer amada), Roberta Lavadour's 2008 glass book Relative

Memory II, and Milwaukee artist and UWM BFA grad Taylor Easton’s 2011

one-of-a-kind fiber and mixed-media piece A

Self Portrait.

What more can you tell us about your experience with the

Look Here! project?

The location of our show at the Villa Terrace

helped solidify my ideas. When we toured

the space and I learned that the room with the Madonna niche is called "The

Family Room," I instantly knew that my work would have good company, and I

became committed to further exploration of the theme of mothering and

parenting.

x

Tuesday, January 9, 2018

The Look Here! Project: An Interview with Nirmal Raja

This is the third installment in our interview series with artists participating in the Look Here! project. Nirmal Raja is an interdisciplinary artist living and working in Milwaukee. She received her Master of Fine Arts degree in painting and drawing at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. She was a mentoring resident at RedLine Milwaukee, an urban arts incubator, for over 6 years. Currently, she works out of her studio at Material Studios and Gallery in downtown Milwaukee.

Asia from as early as the 1500s and into the 19th century; in addition to

travelogues by early explorers of the East. The commentary and the

images in these books are fascinating peeks into what caught the eye of Western explorers. There is a first edition travelogue by American painter Edwin Lord Weeks who focused on painting the people and places of Afghanistan and India. All the material I’ve been looking at so far is what we would now call “Orientalist.”

Why

are you interested in participating in the Look Here! project?

We don’t look at history enough and libraries are

repositories of histories among other things– our relationship with libraries

in general has changed so much because information is available seemingly so

easily. But it’s wonderful being able to wander in an actual physical library

and being able to find things you wouldn’t necessarily find with keywords.

Additionally, to have some guidance is great! I’ve always noticed

that once I start digging into a concept or subject matter for my artwork it

seems to divide its self, as if it’s this never-ending tunnel that you get

into. It’s exhausting in some ways, because then you think that you don’t have

a resolution. But also just incredibly fascinating to see how much information there

is to absorb.

I really started to think of my artwork as a process of research

in graduate school; it’s great to tie that aspect of making with research in

knowledge bases and how those can be intertwined. With this project, I am

referencing or in conversation with the past, and figuring out how to bring the

past to light somehow; processed through my own lens. It seems like any

material can be reframed by who is speaking to it, and we could use that

framing power as an artist to create a space for examination and contemplation.

What collections

are you using or did you begin to use for your project?

Initially I was really taken by the Jeypore Portfolio in the

Special Collections library. I was amazed by the pains someone took to record

architectural details, and the beauty that existed in India at the time; and

the pains that the actual mason or architect took in creating those details in

the first place. This portfolio was my starting point but the project has

expanded since then.

There are certain things that I have tucked away in my

mental notebook to expand on. This project has given me an opportunity to address

a couple of those. One of them is the trope of the screen. In South Asian architecture,

it is called the “Jaali” – it’s been used in South Asian cultures for many,

many centuries as a device for gender segregation, a device for power; so how

do you take something so beautiful and so intricate and decorative and infuse

it with meaning that is relevant to the present, and investigate what’s going

on around us now – that’s what interests me. The screen is also a filtering

mechanism. The person who is surrounded by the screen is looking out on the

world, but also the world is wondering what must be inside. And so I initially

thought that’s what I would be making work about, but it’s expanded. Which is

the condition of research, I guess. Beauty is very much present in my work and

Jaalis are wonderfully intricate and beautiful, but I also seek depth and

meaning in my work. Beauty can be a tool to bring the viewer into the work, but

also to bring the viewer to a different plane, making them think and question.

We’re living in a time of anxiety. It took me a long time

to feel like I belong in this country, only to doubt that again this past year.

I’m trying to figure out how I fit into this dynamic of power, but also what is

my role as an immigrant artist who considers herself American but also from elsewhere.

I think as a culture, we’re becoming very unidimensional. But art can be a

place where we can find richness and complexity, and also where we can possibly

place the viewer in a situation where they have a choice to look reality in the

face or to look past it. I want to use the screen as a place where the viewer

is confronted with this choice.

I will be printing a list of recent hate crimes on vinyl

and having patterns sourced from the Jeypore portfolio cut into this vinyl and

this will be pasted onto the glass panes at the Villa Terrace around one of the

sleeping porches. When the viewer enters this space they are surrounded by a

beautifully intricate screen; with light streaming through it, shadows being

cast. But when they look closely they can read a whole list of recent hate

crimes on the vinyl. This screen will become a frame for some of the artifacts

that I will be curating from the AGSL and the Special Collections library. (note: the Look Here! project will culminate in an exhibit at the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum, opening June 28, 2018)

Max Yela, (Head of Special Collections) has been pulling

out early books by travelers in the 16th century, to the Far East

and South Asia. They are mostly travelogues, but also children’s books – from

the turn of the century to 1930s. It’s interesting to see what kids were being

taught about the rest of the world. The things you are taught as a kid before

you know how to be critical.

Marcy Bidney at AGSL (American Geographical Society Library) has been pulling maps of South

images in these books are fascinating peeks into what caught the eye of Western explorers. There is a first edition travelogue by American painter Edwin Lord Weeks who focused on painting the people and places of Afghanistan and India. All the material I’ve been looking at so far is what we would now call “Orientalist.”

I’ve been interested lately in the gaze and how that could

possibly be expressed or represented. Orientalism in a sense is an expression

of the gaze, so you’re looking at the East and this certain notion that it’s exotic

or savage and there is an implied power play that cannot be ignored.

Representation or even looking is an act of power, and if a certain way of

representing becomes the only way, then the subject loses their power to

represent themselves. My effort to dig into some of these older publications

and objects is to understand how the East has been represented and understood in

the West over the centuries and how that might influence perceptions of those

cultures now.

But then what do I do with this information? This knowledge

base is so large, so much has been written about it; there is the sheer number

of books that have been written about the East, but also scholarly works about

Orientalism.

I decided to facilitate an experience through an installation

of curated objects framed by the screen in a specific way. I am using the

screen as a tool for gazing and placing the curated objects in the context of the

present. The viewers are left to decide for themselves what they want to look

at. That’s my idea… so let’s hope it succeeds! You never know with artwork –

but in general it seems like once I have a direction, the work seems to make

itself.

How

does having so much content available digitally affect the work you're

creating? Or does it?

I’ve been browsing photographs in the digital collections,

especially the AGSL photo portals; and some of the maps are digitized as well.

I think for me this project itself has a lot of potential digitally. You’ll be

creating a digital database based on this exhibition and that’s kind of

fascinating to see how my work will eventually exist in a digital space.

Having the Jeypore portfolio digitized makes it possible for

me to create the screen, create the vinyl; it’s not possible otherwise to make

this work. Some of this almost seems like a given now; the digital lies

underneath the work, it enables the work but it’s sort of the unseen labor

maybe. And the archiving capacity – for example, the whole content of the hate

crime list that I am using is on www.saalt.org. That

would not have been possible before the digital – the network enables this kind

of sourcing and documentation.

The other thing that’s digital is the music – converting my

great uncle’s records from the 1940s to the digital was an interesting process

to watch. Because the music has to be played on its original medium, it has to

be captured in a way where the digital is forced back into the analog world.

Sticking the digital microphone right in the horn is the perfect juxtaposition.

A: Would you say that what you're doing is an act of curation as opposed to an act of hand-making, perhaps?

The work is very much in process, in a research stage. I

haven’t really made anything yet. The making will really just be a culmination

of this whole project. This is the first project where I am not really creating

with my own hands – Which is really

strange for me. I’m working from a digital copy of the portfolio, a machine

does the printing, and the cutting is done by yet another machine. It’s like

being the director/producer. It’s interesting...

=========================

More about Nirmal Raja's work can be found at her site, http://www.nirmalraja.com/ and at her Instagram site: https://www.instagram.com/nirmal.raja/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)